Being outcompeted by suppliers

It's long-term trouble to be running a business where your competitors control the cost of your product. This didn't end well at my previous employer, and won't end well at some cloud data warehouse companies either.

Summary: It's long-term trouble to be running a business where your competitors control the cost of your product. This didn't end well at my previous employer, and won't end well at some cloud data warehouse companies either.

Lesson learned from my previous employer

Once upon a time, in 2005, a computer storage company founded by an old friend and colleague of mine, David Flynn, built the first working enterprise SSD in a time where everyone else was failing. The company was called Fusion-io, and its revolutionary product was called the ioDrive. NAND flash was starting to become popularised by consumer devices such as mobile phones, capacities were starting to increase and prices were starting to drop. Some companies including Intel had tried to build enterprise-class storage drives (hard drive replacements) around NAND flash, but connecting them through SATA which acted as a serious performance bottleneck. By connecting the Flash to the PCIe bus and building a log-based flash translation layer in software, Fusion's ioDrive supported tens to hundreds of thousands of IOPS. Business boomed because the technology enabled hyper-scalers such as Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Tencent and Alibaba to grow faster.

Over time, prices of the Flash media continued to drop: What was $20/GB then became $0.20/GB today. The factories (fabs) that supplied the Flash memory, like Samsung, Intel, Hynix, Toshiba and Sandisk, wanted to build SSDs of their own. After a few years, they too perfected the software and used the PCIe bus, and introduced an interoperable standard called NVMe. The fabs undersold Fusion-io because they had a shorter value chain with less margin stacking, Fusion-io couldn't grow and was itself sold to one of the fabs.

All about margin stacking

If I'm a company building and selling any kind of product, gross margin really matters: It's what the value I added to the product is worth to the market and is reported as the percentage that I make on the product sale:

Gross_margin_percent = 100 * (profit / revenue);In a simple example, if I buy raw materials and use them to build a Gizmo for $1 then sell all of it to Acme Ltd for $3, I have a 66% gross margin. That's a pretty good margin in computer hardware, it's attractive to investors, and it also turns out it's a pretty good margin in cloud services too.

In reality though, the 'value chain' — the path from raw materials to end customer — is much more complex, and at each step of this chain, margin is added. This is what we call 'margin stacking:' Let's say Acme Ltd wants to sell the Gizmo on to an end customer, perhaps branding it as Acme-Gizmo+ and adding some sexy packaging. Acme buys the Gizmo and tarts it up to make the Acme-Gizmo+. Acme also wants to make its 66% gross margin, so it takes the Gizmo, puts in $0.20 of work for branding and packaging, meaning its total cost is $3.20 — and then sells the Gizmo to the end customer for $9.60.

This is why basic goods sold in the West are so expensive, despite them being made in China so cheaply — and why import tariffs didn't make a whole lot of difference. The amount of margin stacking from Chinese factory floor to Western customer is so substantial, adding tariffs earlier in the value chain made little difference.

From Flash value chain...

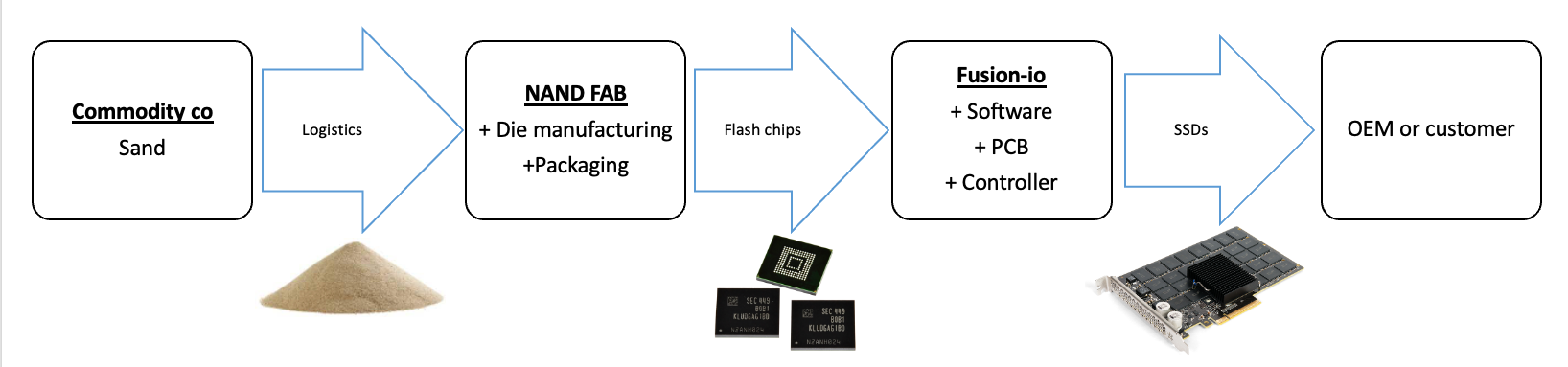

A simplified value chain from Fusion-io looked like this:

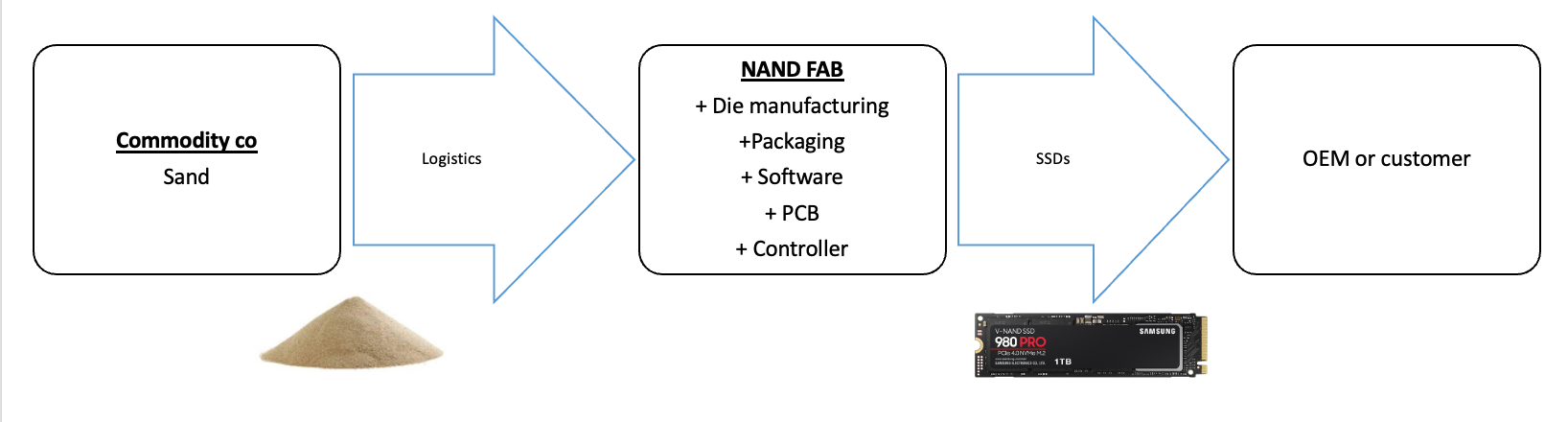

The NAND fabs controlled the price of the chips purchased by Fusion to make SSDs. When the NAND fabs learned to make SSDs themselves, they wouldn't lower the price of the NAND chips to Fusion-io; instead they sold whole SSDs for not much more than the price of the chips:

One less layer of margin stacking made the products almost 3x cheaper to end customers. Fusion's business model became unsustainable. It's as though the Gizmo company learned how to do good branding itself, cut out Acme, and sold direct to the customer for $3.20 each. Nobody wants to pay 3x more for the same thing.

Cloud Data Warehouses and Snowflake

This brings us to what's happening in the data warehouse industry. The cost of cloud compute and cloud storage continues to drop, and with each year database software becomes increasingly more efficient: More efficiency means less money spent on compute and thus savings to the customer.

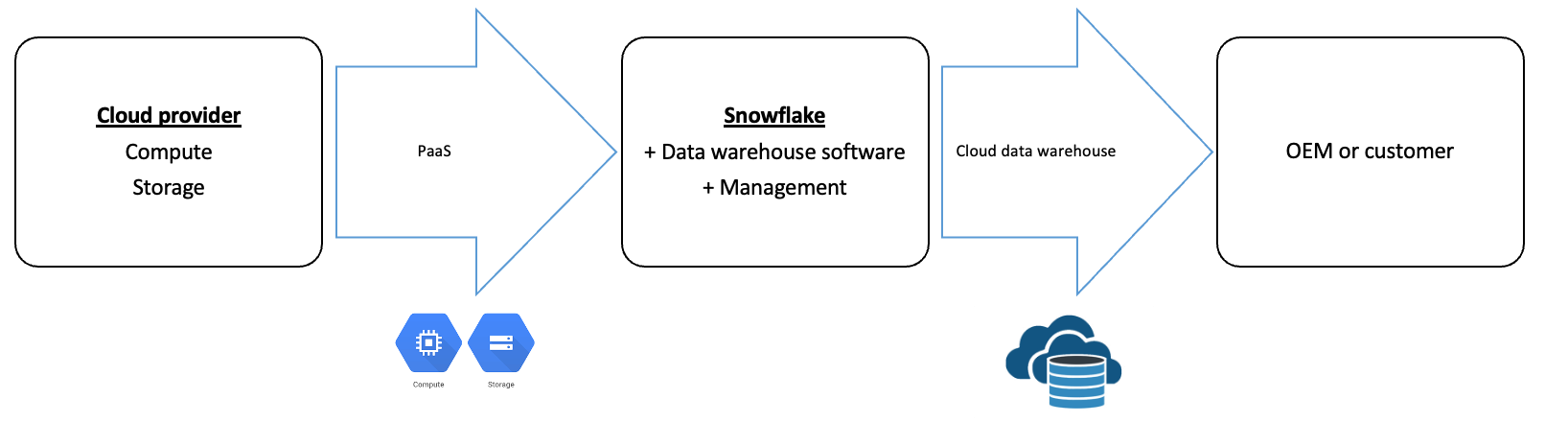

Snowflake has a wonderful data exchange and data sharing ecosystem, however while it focuses on its war with Databricks in machine learning, more and more of their customers are becoming concerned at the cost of the core database engine itself, the credit-based business model that discourages extra consumption, and the lock-in business practices. There are a great number of similarities between this and the Fusion-io world. Snowflake's biggest competitors are Amazon, Google and Microsoft; Snowflake, to operate, also resells storage and compute at added gross margin from Amazon, Google and Microsoft:

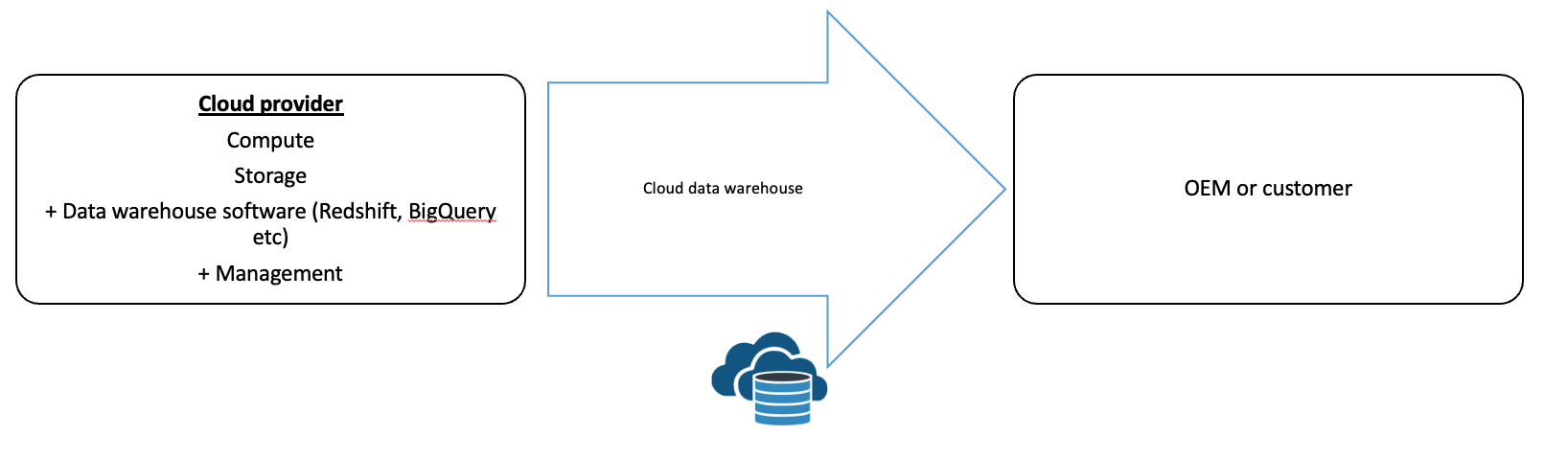

In some cases, the cloud providers can undersell Snowflake themselves, by doing a simplified value chain with less margin stacking and the advantage that there's only one vendor to deal with:

This however has all the disadvantages of a single-cloud data warehouse: The warehouse is coupled to the cloud. Companies looking to minimise cloud concentration risk are unable to put all of their eggs in one cloud vendors' basket To date, the only solution to this dilemma has been to buy Snowflake. However, cue Yellowbrick with a new business model:

Yellowbrick value chain

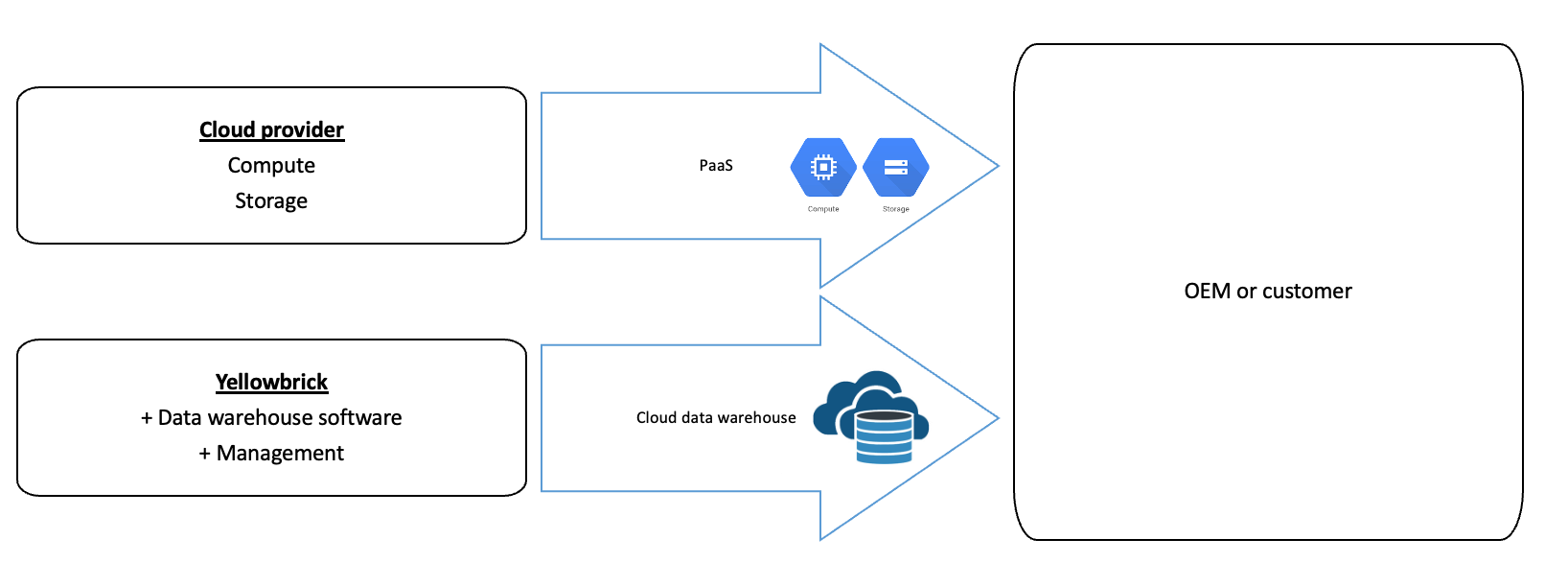

At Yellowbrick, we sell data warehouse software to our customers that provides all the ease-of-use advantages of Snowflake, but without marking up cloud providers' infrastructure:

Our customers buy their own storage and compute from their cloud providers (or, from hardware providers for on-premises users) and database software from Yellowbrick. The Yellowbrick software is sold without marking up underlying infrastructure, allowing Yellowbrick to make a high gross margin. The customers pay their own negotiated rates with Amazon, Google and Microsoft — sometimes including free storage – for their cloud infrastructure, which are almost always lower prices than Yellowbrick could buy them for anyway.

This cuts an entire step out of the value chain and allows us to offer a Snowflake-like database user experience but with added benefits apart from just cost: Customers' data stays in VPCs that they manage, allowing them to better control their security and access and allowing them to take into account all regulatory and data sovereignty concerns. The sign-up experience is as simple as a few clicks of the mouse.

Conclusion

Shrinking value chains — going direct to customers, bypassing intermediaries — has always been the foundation of truly disruptive businesses, from Dell to Uber and Lemonade. At Yellowbrick we've done this with the cloud data warehouse, and also done away with the lock-in business practices and ahead-of-time credit purchases. We've done our best to try to make an open standard, too, by retaining PostgreSQL compatibility on the outside. We've built a lower cost, altogether more business-friendly and more interoperable data warehouse and avoided the classic trap of our competitors controlling our costs.