Superior stock and derivatives

Below are instructions for making a basic superior stock; refining it into a crystal-clear consommé; and using the leftovers to make a white concentrated stock.

Stocks are used to give flavour to all manner of food in the Cantonese kitchen. High quality stocks are expensive to make, both in terms of elapsed time, energy consumed and the cost of ingredients. Only the very best restaurants or seriously dedicated home cooks can afford the time and effort needed to make wonderful stocks. In other cases, the flavours afforded by great stocks are instead approximated.

In fine cuisine, high quality stocks are used for the soup in a dim sum soup dumpling (灌汤饺); for making poached, healthy green vegetables; for mixing into eggs for steaming; as the base of the sauce for ginger/scallion stir fried lobster; for serving the famous boiled cabbage (开水白菜); as the primary ingredient in the soya sauce served with your steamed fish; for making brown sauce for cooking prized ingredients; as a basis for other soups; etc. It's one of the key differentiators between Cantonese fine restaurant cooking and the rest.

Cantonese stocks differ from the French-type stocks by including more protein-rich ingredients and whole meats along with less vegetables. Most superior stocks include chicken, ham, and some other meats. Some recipes from different regions or chefs may use more types of pork bones, perhaps some duck or even a leftover head from roasting a goose. Cantonese recipes will include some sort of dried seafood which contributes a savoury sweetness to the soup. The ham brings a little smokiness and saltiness, and the chicken is the base taste. This can be further refined by using old hens and/or younger chickens. Some chefs will add other dried ingredients or spices in small quantities such as longans to add sweetness or peppercorns.

The resulting stocks are not watery “bone broths” or anything like the stuff out of tins or cartons in high-end supermarkets. Even those expensive, high end stock brands from high end butchers tend to be crap by comparison. The proper superior stock feels rich and silky in your mouth and coats your tongue. When the stock has been well made, it needs no seasoning whatsoever to taste good on its own in a bowl.

Lower-end restaurants will just substitute chicken powder and water for stock. Of the many brands of chicken-flavoured powder I’ve tried - from the US to Hong Kong to Europe - by far my favourite is the Ajinomoto brand. Of course, it includes MSG, but also tastes quite good and has a nice colour. Next would be the Lee Kum Kee chicken powder, then maybe the Hong Kong Swanson ham bouillon cubes, the usual suspects. Agressive use of this "chicken powder" (鸡粉) does the job, makes something taste OK but is in no way comparable to the sophistication (or health) of the real thing. The next step up would be to consider using some canned or boxed chicken soup. A lot of restaurants use this to serve noodles and the like, but I find that Ajinomoto chicken powder actually tastes better.

I'd much sooner eat less processed food, and make it myself. Here's how. Below are instructions for making a basic superior stock; refining it into a crystal-clear consommé; and using the leftovers to make a white concentrated stock.

It should be noted that there is no “right” or “wrong” recipe for stock making. Chefs will have their own approaches and recipes. These are simply the ones I like to make, that suit my taste, and are based on learnings from various Cantonese chefs, cooks and restaurant owners over the years. The resulting stocks are absolutely comparable to those in high-end restaurants although perhaps still not quite up there with the Michelin best of the best!

Simple stock

If you want to start making soup, the easy way is some sort of leftover bones and bits from chicken, pork or beef left boiling on the stovetop. It can be boosted by using the water remaining from poaching or boiling meats for use in other recipes. This will make a decent enough stock given enough boiling time and adds a basic flavour to any dish. Take that further and use whole meats and start to add in some more precious ingredients and now you’re talking.

Making superior stock (上汤)

Although a simple stock can be made by just boiling some bones in water left over from poaching other ingredients, a superior stock starts with superior ingredients. To make this, you need either a burner with really good control that can keep liquid just below a simmer for hours; or a stock pot that can fit in a bigger stock pot (aka a double boiler); or a steamer. I use a double boiler by putting a big stock pot into a steamer.

Ingredients

Clockwise from 12 O'clock, these are the ingredients in the picture above:

- A handful of dried scallops

- 1 large dried squid, soaked in warm water for a couple of hours

- 0.5kg lean pork, cubed

- 0.5kg Iberico ham bones (from R Garcia and Sons in Notting Hill)

- 0.3kg Jinhua ham, cubed

- 1 young chicken

- 1 old hen

- 4 spring onions (not in the picture)

Philosophy behind these ingredients: I prefer a chicken- and seafood-forward soup with less pork meat, since I don’t like the taste of pork as much. I don’t add ginger, sweetness, seasoning or any other dried things because I find it unnecessary.

Preparation

Soak the dried squid in warm water until soft. When soft, remove the beak, any gnarly bits, and pull and scrape the skin off the dried squid. Cleaning and skinning the squid is really important otherwise it contributes unwanted fishiness to the stock. Cut the arses and toenails off the chickens and throw them away, chop them up into bits, removing any excess fat or bits of organs as you go. Leftover fat can be kept and rendered for stir-frying vegetables. Chop the lean pork and ham into cubes. Rinse all the ingredients.

Warm then re-wash the raw ingredients

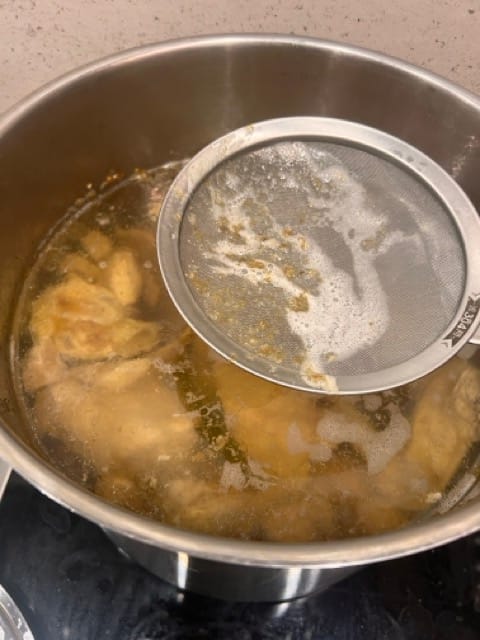

Put cold water in a stock pot, a tablespoon of salt, the chicken, the pork and the ham bones. Gently warm up the water till boiling point, skimming off scum (coagulated proteins and other impurities) until the ingredients change colour and scum has stopped oozing out. Don't boil it for more than a minute or so though.

Strain the meats, throw away the water, and wash the meat thoroughly under cold running water, getting your fingers into all the joins to make sure they are clean of scum. Clean the stock pot.

The long cook

Put four spring onions across the bottom of the stock pot to help make sure things don’t stick. Layer in the ham bones, then half the meat (in any order), then the dried seafood, then the rest of the meat. Add enough cold water to cover the ingredients plus a centimetre. Put the stockpot onto the stovetop, bring almost to boiling point, and keep it below boiling - so the water barely moves - with the lid off for an hour, repeatedly skimming any crud off the top.

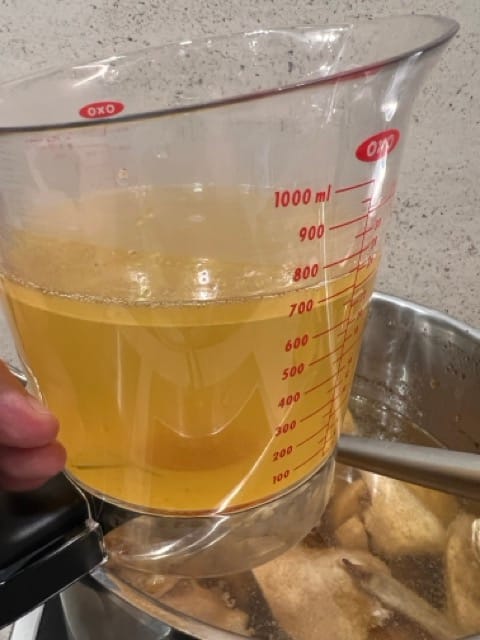

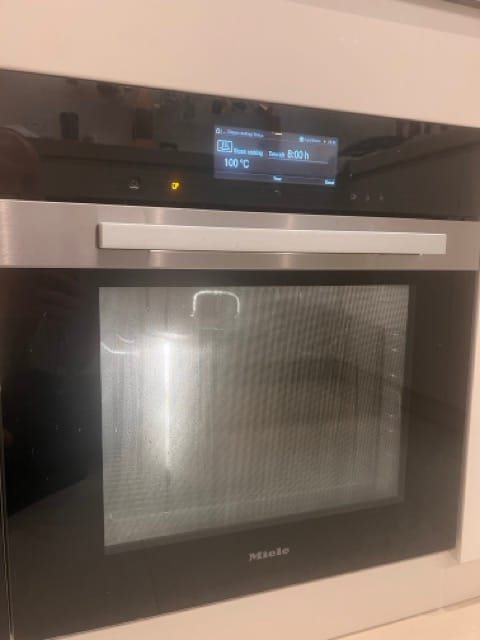

After an hour, use a gravy separator to take any fat off the top. Put the stock pot into a large double boiler (or steam oven) with its lid on, and steam it for a further 8 or more hours.

Skim off crud, separate off any fat after an hour, then double boil for at least 8 hours

Double boiling keeps the liquid at a perfect temperature: Hot enough to make great soup but not to boil or agitate things, even with the lid left on. Liquid will be retained well. If you have to keep it on a stove top for 9 hours, heaven forbid, leave the lid off, keep the temperature low and add a little water if the water level starts to sink much below the level of the ingredients. I normally do this step overnight and check on it in the morning (not a good idea if on an open stove) which means the actual cooking time for the stock is more like 10 hours.

Strain the stock

Take the resulting stock, again use a gravy separator to remove fat, then strain it through a cheese cloth into a bowl, retaining the leftover ingredients for a concentrated second stock outlined below. The resulting soup in the bowl is a slightly cloudy and incredibly tasty superior stock that tastes wonderful, which can be used as is, or refined to a clear stock for presentation purposes by following the next steps.

Making refined stock (吊汤)

The highest level restaurants will take the superior stock and clarify it using lean proteins to make a stock that has the same, intense flavour but is almost completely clear. It comes out looking like a French consommé but with a more sophisticated taste. This is called diaotang (吊汤) or refined stock.

Ingredients

- The superior stock from above

- 2 boneless, skinless chicken breasts

- 2 egg whites

Instructions

Dice or coarsely blend the chicken breasts and the egg whites to make a yucky pink paste. Don't pulverise it completely, you want some small lumps in there - a few pulses in a food processor will do.

Return the superior stock above to a cleaned stock pot, without any of the leftovers. Skim it again (not yet done in my photo below). Massage a cup of water into the pink paste by hand to loosen it a bit. Pour the pink paste into the stock pot and whisk it into. The whole thing will look gross, like a giant pot of pepto bismol (“Oh no, I’ve ruined my stock!”).

Turn the heat on very low, and very slowly bring the stock pot to a boil. Stir the stock very gently, around the bottom of the pan, to make sure nothing sticks. All the proteins will be on the bottom, so if you heat it too fast without any movement, chances are you'll get burned stuff on the bottom and ruin the whole thing (I did this once and had to throw it all away and start again).

As the stock heats up, the chicken breast and egg whites will rise to the top of the pan, forming a raft. As the proteins coagulate, they will attract and trap fine particles, fats and other impurities in the stock.

The clarification process

When this process is complete, Use a fine mesh filter to make a hole in the raft, turn off the heat, then use a small ladle to remove the refined stock. Any remaining, hard-to-collect liquid can be added to another bowl to make the second stock below, along with any liquid extracted from the raft by squeezing it in a cheesecloth when cooled.

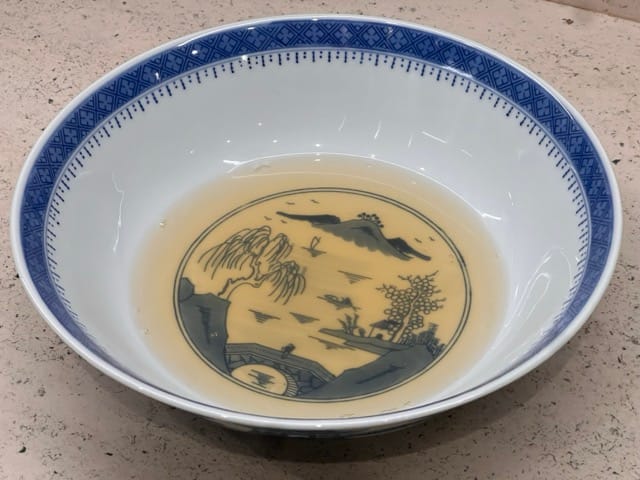

The refined stock can then be frozen in ice cubes for future use, or drank as-is. It will be beautifully clear - if somehow it isn't repeat the clarification process a second time after the soup calls. Here's a picture of the stock in a bowl with a pattern on the bottom:

Second stock, concentrated (濃湯):

After the previous two steps, we've got a lot of leftover boiled meats and dried seafood with only a fraction of their flavour remaining. The traditional option is to make a weaker second-derivative stock (二汤) by just re-boiling it over a high heat, but I learned a better alternative: Make a rich, concentrated stock, nengtang (濃湯) by making use of the fact that fried, browned proteins will emulsify beautifully when boiled.

Ingredients

- Cold leftover meats and dried seafood from the superior stock

- Leftover stock liquid from the bottom of the stockpot and anything squeezed out the raft in a cheesecloth

- 12 chicken feet, de-clawed and rinsed

- Optional - a handful of cheap frozen fish maw

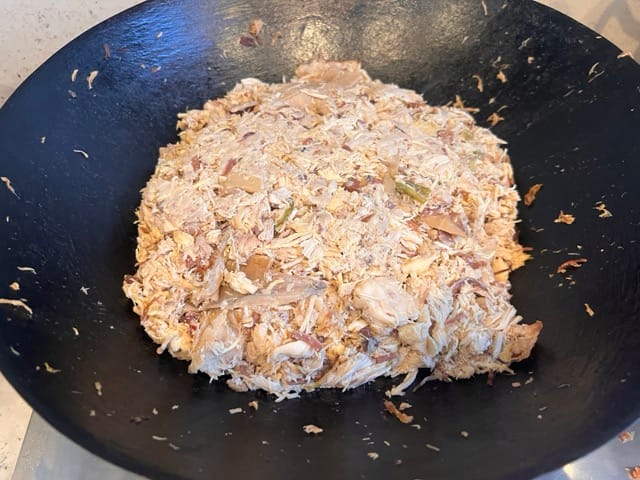

Preparation - making meat floss

Squeeze as much liquid as you can from the cold leftovers and add to the stock liquid. Then remove any bones from the leftovers by hand, shred up the bits of flesh like making dry "pulled" pork and putting them into a dry iron or steel wok without oil.

Turn on a low flame, and dry-fry the meat floss. No oil is required because there are still some oils left in the meat. Turn up to a medium heat and keep stir frying the meat floss until it browns and crisps ever so slightly. It might stick initially but won't after a while, just keep scraping it off and turning it. The lightly browned crunch bits add flavour to the resulting stock. Whatever you do, absolutely do not let let the wok smoke and do not let any of the floss burn - if there are any burned bits or even smoke from burning, the resulting stock will taste disgusting. This isn't a time for practicing "wok hei" since things will burn very easily.

This continuous stirring turns out to be pretty hard work, since the meat floss is initially heavy, but it gets lighter as more moisture evaporates. Stop when the floss is light, fluffy and has some golden brown bits.

Make the soup

Prepare a kettle full of boiling water and any additional superior stock liquids (it works out about one ladle full for me). Turn the heat up to high for a moment then pour over enough boiling water to cover the floss along with leftover stock liquids. Throw in the chicken feet and (if using) frozen fish maws.

Boil the stock vigorously in the wok until it turns fully white, at least 20 minutes. Then let it boil slowly for up to an hour. Keep adding boiling water if the water level falls below that of the floss.

Turn off the heat, strain through a fine-meshed chinois sieve, using force to extract as much liquid out of the remaining meats as possible.

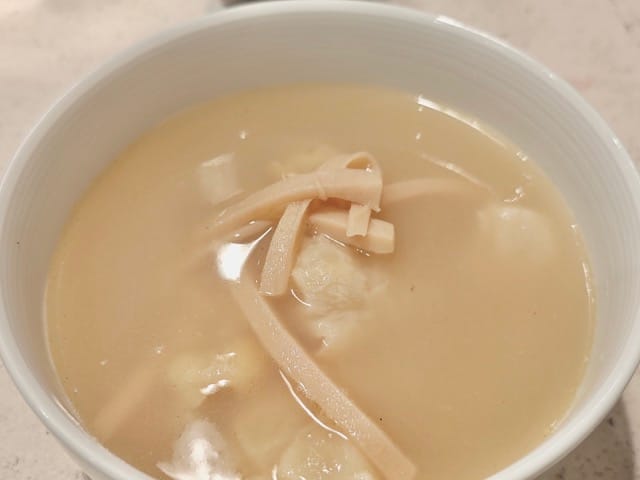

The remaining stock is creamy white in colour, thick, gelatinous and very flavourful. Wastage of ingredients is minimised. It is brilliant as a basis for fish stock, a fish and tofu soup, fish maw soup, dried sliced abalone soup (鲍片汤), adding to the water when boiling a rice congee, poaching clams or serving alongside poached vegetables.

Put it into a bowl, refrigerate it overnight, then cut up the resulting block of jello-like thick stock into pieces and freeze it.

Here's a picture of a soup made with a small amount of the concentrated stock, additional water added, some white pepper, abalone slices, a little dried fish maw and basic seasoning. It tastes fabulous!

Summary

I've shown how to make superior stock, clarify it into a high grade consommé, and use the leftovers to make a concentrated stock that can be used in a variety of dishes where clear soup isn't called for.

It's well worth doing this - not to use in day to day cooking, but to have on hand for when special occasions merit cooking amazing food for friends, family or loved ones. Or when feeling like a quiet night in and eating something special.

The stock concentration technique outlined works brilliantly for ultra-rich chicken stock as well: Follow the same process to chop up a chicken, do a first boil, wash it, boil it again for 3 hours until the meat falls off the bone. Save the broth, shred the meat, remove the bones, dry fry it into chicken meat floss, then pour back over all the chicken broth and boil it for a while. A rich, yellow coloured chicken stock will result which can also be frozen and used in other soups, pastas and dishes.